There is an iron rule in the world of collecting: no matter how priceless or unique your collection is, you must be able to endure loneliness, especially if your collection might be of dubious origin. If you genuinely love the item, it is best to hide it deep, appreciating it privately with only yourself and trusted friends in the circle; if you only value its “worth” and hope to sell it for money to live lavishly, then you must conceal your identity and dispose of it discreetly, ensuring the buyer is also someone who can keep a secret. Otherwise, if they suffer, you will be implicated.

However, the Chinese cultural relic collecting community has a bad habit: they particularly love to show off. Once they acquire a “good item,” they are always impatient to tell others, invite people home to admire it, or even loudly announce it to the world, afraid that others won’t know their taste and capability.

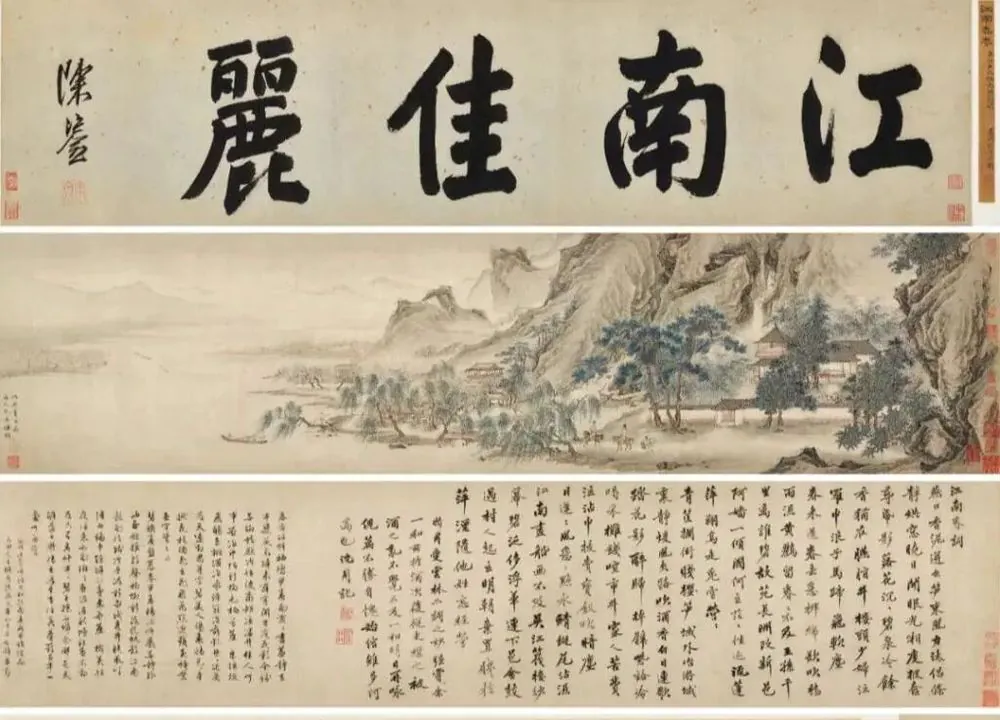

Unfortunately, Lu Ting (陸挺), the original owner of Jiangnan Spring (《江南春》), was not a low-key person during his lifetime. He had long declared publicly that he held Jiangnan Spring and had invited people to view it. The medal in his hand finally turned into a bomb.

In 2010, Lu Ting’s “Yilanzhai Art Museum” (藝蘭齋美術館) in preparation for its upcoming inauguration, specifically displayed Jiangnan Spring among its collection to a reporter. In the article, “A Secret Exploration of Yilanzhai’s Treasures” (《藝蘭齋珍寶探秘》), the reporter also wrote a passage introducing how Jiangnan Spring was passed down to Lu Ting’s “Yilanzhai”:

“The person in charge of Yilanzhai produced a photocopied letter from the Shanghai Museum. The letterhead was stamped with ‘Social and Cultural Affairs Bureau of the Ministry of Culture of the Central People’s Government'(中央人民政府文化部社會文化事業管理局) . This was a letter written in 1953 by Zheng Zhenduo (鄭振鐸), then director of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, to his old friend Xu Senyu (徐森玉), head of the Shanghai Cultural Relics Management Committee (上海文管會), stating that the Palace Museum (故宮博物院) was short of paintings and calligraphy from the Ming and Qing dynasties and asking him to solicit paintings. Among those listed as ‘absolutely necessary’ by Zheng Zhenduo was Qiu Ying’s (仇英) painting Jiangnan Spring, collected by the famous collector Pang Laichen (龐萊臣).”

This passage was as good as unwritten. Even though the letter produced by the person in charge of Yilanzhai had the impressive signature of the “Social and Cultural Affairs Bureau of the Ministry of Culture of the Central People’s Government,” the letter only stated that the Chinese Ministry of Culture at the time wanted Jiangnan Spring, but did not explain how Jiangnan Spring ended up in Yilanzhai’s hands. What is even more suspicious is: how did a cultural relic desired by the state end up in Lu Ting’s possession?

Even more ridiculous is that in 2015, when Pang’s descendants sued the Nanjing Museum, the curator Pang Ou (龐歐), who was the defendant, used this report as evidence to prove that Lu Ting and his wife from Yilanzhai had purchased Jiangnan Spring as early as the 1990s. This report buried a nuclear bomb for today’s exposure of the matter. The report described the box containing Jiangnan Spring in great detail. Pang’s descendants stated that the box was the original one from Pang Laichen’s collection, and this matching box was also clearly recorded in the donation list provided by the Nanjing Museum (南京博物院) that year.

A collector in Shanghai, in an interview with The Paper (澎湃新聞), claimed that he had seen Jiangnan Spring at Lu Ting’s home in 1999 when he went to demand repayment of a debt from Lu Ting. At the time, Lu Ting might have been unable to suppress his desire to show off, or perhaps he wanted to indicate to the person demanding payment that he was not without money to repay. In any case, he voluntarily showed this sensational collection to the visitor and said that the painting was sold to him by a descendant of Pang Laichen, who was studying at Nanjing University and sought him out after hearing his reputation. Lu Ting’s wife, Ding Weiwen (丁蔚文), also stated in her academic paper, “Textual Research on Qiu Ying’s ‘Jiangnan Spring’ Scroll” (《仇英“江南春“卷考辯》), published in the Journal of Nanjing Arts Institute (《南京藝術學院學報》) in 2007, that her husband’s collection of Jiangnan Spring was purchased from Pang Laichen’s descendants.

The Yilanzhai Art Museum has yet to open, and Jiangnan Spring remains a legend. The cultural relics circle is small, and people might not have taken it seriously, thinking Lu Ting was just bragging. However, after Lu Ting’s death in May 2025, the successor, Zhu Guang (朱光), immediately put Jiangnan Spring up for auction, as if he couldn’t survive one more second without getting his hands on the 80 million yuan. Is there a possibility that they had an agreement during their transaction that Lu Ting could not publicly sell it while alive?

According to The Paper, Lu Ting had mortgaged Jiangnan Spring and other collections to a company due to a loan. Later, unable to repay the debt, the mortgaged painting was resold by the company to the current holder, Zhu Guang. Zhu Guang is not a well-known figure in the collecting world. He only switched to buying and selling paintings and calligraphy a few years ago and has lived abroad for a long time, possibly unaware of some of the unwritten rules in China’s domestic collecting circle.

The explosion of the Jiangnan Spring incident finally uncovered an embezzlement that spanned over 20 years, all thanks to this collector who was eager to exchange the painting for cash. Lu Ting is dead, free from all worries. Pitiful is Xu Huping (徐湖平); people forgot that he is still alive. An 80-year-old man who served a few years in the military in his youth, his body is probably still robust. In his later years, he had been so low-key that he only won a Forbes-rated Outstanding Cultural Figure award last year, occasionally appearing on Douyin (TikTok) where people would film his home filled with rich collections of paintings and calligraphy. But how can he withstand having his reputation tarnished in his late years?